集中營記(一)

陷入戰爭中

1941年十二月,日本偷襲珍珠港後,在中國的佔領軍將盟國人民拘禁,集中在山東濰縣(今濰坊市),上海和香港三地。

本文是作者本人暢述當年入營前後以及在營中親歷的事跡,並非一般創作供消遣追的小說可比。

讀後我們得以了解西方人精神優越的一面──饑餓下不忘教育了子弟和追求學問,服務不計報酬之有無,患難中保持合作和友愛──

信心乃是人類前進和向上的原動力。

戰前,內陸各省有“中日內地會”創設的學校(神學院在內,共約二百間)診所,教會,宅院等,其教士的足跡遠及內,外蒙,新疆,西藏,青海等地。該會創辦人是戴德生牧師。本文作者為戴德生當年僅八歲的重孫女,今是作家,講師,現任美國紐澤西州坎埔頓青年中心的主管。

抗戰末期,譯者一度身為日軍的囚徒,幾乎被遣北海道去充當奴工,幸蒙友好及時相救,始免於難,因此讀本文時,感懷倍增,而獲益至深。本文於1985年八月間在費城首次發表,今經作者同意,譯成中文,使英,漢合併付印,介紹給中文讀者。原作的文字優美而深邃,譯文難期表達原韻,故盼讀者先讀原作,拙譯僅可當作參考。由於直譯與譯意兼取而外添語句俾利表達,未盡符合原作或欠通順之處在所難免,敬希涵諒。

英文原作的版權仍由作者自己保留。

-譯者 曲拯民 謹識

飛機掠過低空,機腹裂處,白罌粟花似的降落傘搖晃着徐徐下降,相繼落在俘虜營外的田地上。美國的空降兵到了!

這是1945年八月間的事,地點在山東濰縣的“平民集合所”日本人叫它做“集中營”。那年我正十二歲,自入營迄解放之日,我和姐,哥,弟一共四人,在日軍的拘禁之下,度過三年犯人的生活。算來,我和父母親由於中日兩軍戰線對峙,雙方相隔的日子是五年半。

平時,大門是絕對禁止出入的,今見美國士兵空降,大家便不顧一切,潮水一般湧向門外,此時禁錮我們的圍牆已失去作用。我夾雜在呼喊,或喜極而泣,看來個個瘦弱,衣服綴着補釘的男,女,孩子們所集成的人群裏,爭先恐後地衝出了大門。其中有英國人,美國人…一同對自空降下的士兵發出了狂熱式的歡迎。此時日本崗兵已將武器放下,任憑我們,因為戰爭已經結束了。

凱琳,雅各,約翰和我,是美以美會傳教士的兒女。日軍將我們全體同學和老師們從中國東部的煙臺強迫集中,終運此地拘禁之。中日戰爭發生不久,我的父母,戴永冕牧師夫婦,逃過日軍防線,進入中國的大後方在西北工作,直到戰終,因此和我們分離了。

戰前,我曾在一個富傳奇,人們相信古老佛教之區域渡過童年生活,所聽的是廟堂簷下風中的鈴聲,所見的是樸實農夫們扶着犁在田間耕種。不料在中國海的彼岸,興起一夥野心勃勃,圖謀向中國土地伸展的軍人,他們高唱“亞洲地土應屬於亞洲人”的口號,在中日提攜的原則下,滿洲全部應由日本管理。

1931年,他們在滿洲發動了“事變”。不到六個月,就佔領了全境,並成立一個傀儡政權供其驅策。此後逐步侵略着中國的國土,正如邱吉爾所說“逐葉而食”之喻。可惜列強中無一國家肯挺身而出,用軍事行動來制止侵略。

日軍剛佔河南省時,我父母即感到勢難在高傲的日本佔領軍下繼續工作。每天出入城門的過路人必須下車向他們鞠躬為禮,這是日軍的命令。有兩次,我母親從腳踏車下來遲了一點,衛兵就用手中的小棒棍打了她的頭。

本文作者入讀

“芝罘學校”之前

值此局面下,父母便帶着我和弟弟約翰一同到煙臺去入學,藉作暫時的休息,換換環境。此時姐姐凱琳,哥哥雅各已是該校學生。

中國內地會在煙臺設立的中小學,簡稱“芝罘學校”,(芝罘又名煙臺,市之北有半島芝罘,古時寫作之罘,名見史記。昔日秦始皇三次東巡,曾刻石於此,並在附近射鮫魚。明代防倭寇時,設千戶所及烽火臺於此,故煙臺之名稱始於明代。─譯者)是一道地英國式學校,設立的目的在方便所有在中國傳教士的子女,不必返回自己的國家去受教育。學校初創時僅有課室十間,外加廁所,及至我們入學,早已大加擴建,儼然一現代化校園。它還有一特點:地臨海濱,這原是教職員夢想中的至佳環境。

記得,當日軍進佔學校的那天,我們的老師正在教我們拉丁文名物字的第四格式,課還沒完,他就低聲說:“我們的新統治者來了!”

頭戴鐵盔,胸佩勳章,腳穿高皮靴,槍上裝着刺刀的日本兵在校外的馬路上把崗,走起路來腰間的佩刀一搖搖地。

自海上一艘航空母艦起飛的一架飛機正在撒下“東亞新秩序”的傳單。

日本軍即將登陸保護日僑民。日本軍的紀律嚴明,必定保護所有良民。各在職的公務人員務須謹守秩序,人民和平相處。日本商人不久將恢復營業,帶來商業繁榮。各民家須懸日本國旗,以示歡迎。

日本軍大本營

當年芝罘學校的女生宿舍

亞洲的新秩序進入煙臺並未遇到強烈的抵抗。

我母親原具教師的素質,她堅信那用心強記的教育原則。縱處於戰爭,飢餓,焦躁,疑慮的逆境下,她總教導我們去依靠上主和祂的應許。她認為抵銷這一切最好的方法就是將聖經上的“詩篇”配上音樂每天唱出。因此,當日本戰艦停泊港口,離我們住處不速,在學校背後通鄉區的大路上抗日的游擊隊常常出沒於夜闌人靜展開攻擊之際,母親就教導我們學習她將詩篇第九十一篇配好的音樂,一家人就在每日晨禱中唱出:

上主是我的避難所,我的山寨,

依靠祂,

不必為恐佈之夜所驚駭…

縱有千人仆倒於左,萬人仆倒在右,

祂必遣使各方護佑…

每次唱至末句:“你不必驚而憂”,歌聲更加昂揚。

在星期日的聖經班上,我們孩子們傾聽老師講述先鋒傳道人那些英勇開拓事蹟。李文斯頓去非洲,帕頓進澳洲東北諸海島,戴德生入中國。

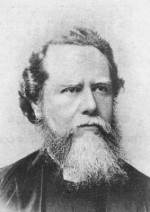

中國內地會及芝罘學校創辦人

戴德生(本文作者曾祖父)畫像

戴德生(1832至1905,享年七十有三,逝世,並葬於中國。他生前有明言,傳誦一時,譯意:倘有英幣千磅,都交中國使用;若有千人,可聘,全為中國服務。壯志由此可見。─譯者)是我曾祖父,二十一歲時決意放棄了他的醫學教育,欲親到中國來實現一個夢想,將基督教傳佈至各省份。1853年(咸豐三年)他啟程來華工作,1881年(光緒七年)創設“芝罘學校”。

他不主張公開集資興募捐,他相信上主會將神蹟奇事帶到人間。

戴德生說:“我並不希望上主派遣三百萬傳教士前來中國工作,可是,不論多或少,祂總會充分資助的!”後來,中國內地會由他組成(1865年),傳教士多至千人,在供應上並無缺乏。

戴德生的家人就在這種堅定信仰氣氛下長成的。我父親是繼曾祖父之後第三代服務中國的傳教士。我們這些孩子們認為父母送我們到芝罘學校當寄宿生然後回到工作崗位上是當然的發展。況且,這場戰爭,中日兩國為敵,英美兩國原是守中立的,(原文作者之父為英國人,母為美國人。─譯者)本不直接干係我們的事,是年我七歲,弟弟約翰僅六歲。

1941年十二月八日清晨,我們起床後,驚見日軍佈崗於學校通校園外面所有的大門,又在門旁張貼告示:“大日本海軍管理”。日本神社的僧侶隨後在球場上行了一次祝福儀式。此後學校一變而成日本天皇的財產。

校園裏所有的人都起了恐慌不無原因。早飯時間,我們收聽廣播報導,說:美國艦隊在珍珠港被襲起火,繼續焚燒中,英艦兩艘已沉沒於馬來亞海域。這時,我們開了校門看,日軍已把守了每一道門,槍上裝着刺刀,如臨大敵。他們更將我們的校長拘捕,禁止他和任何人接觸。

最近一個月來,我們的拉丁文老師馬丁先生正積極籌備聖誕節慶祝會中一個傀儡戲的節目。馬丁是一位樂觀的人,我們有同一想法:戰爭決阻止不了我們過節的慶祝。他手持牽動傀儡的細繩索,在校園的空場上大踏步伐,傀儡便隨他的動作跳動起來,當着學生和日本兵表演一番。他們見了也不免大笑,和學生笑成一起。人總是一樣,都是有感情的。這一着,我們和日本士兵的關係鬆弛了。真的,有誰還對着那些見了傀儡跳動也會歡笑的武裝士兵害怕呢?

由於戰爭的混亂,附近的中國人民正在忍受飢餓中,竊賊時常在晚上光顧我們的校園。最令我們老師驚恐的事是一天晨起發現女生們的大衣皆不翼而飛。此後,各級任老師輪班守夜,小學部的女教員在就寢前先將曲棍球棒子在床邊放好,以防不測。

話分兩頭。在離我們約七百英里西北方的鳳翔縣(地處陝西,在寶雞市東北約五十華里,係一古城,唐玄宗末期安史之亂平定後,至德二年即公元757年。詩人杜甫在此,朝見肅宗皇帝,官拜左拾遺。─譯者)一名聖經學院的學生在開教職員會時將一份中文報紙交給我母親,那報紙上印着令人震驚的大字標題:

珍珠港被襲!美國參戰!

母親讀畢,嚇得目瞪口呆,真料不到美國也會介入戰爭。她惦念着四個心愛的孩子,會不會有一天被日軍所吞噬。又鑒於凶暴的日軍於攻入南京前後對中國婦女的強姦獸行,她便不寒而慄,終至木然地倒在臥室中的床上啜泣了。

想起往事來,似乎一場舊夢。幼年,在美國賓州威克拜城的一間教堂裏,費貴森牧師曾對她說過這句話:“愛麗斯!如果你對上主所喜悅的人或事盡心做出當做的工作來,那麼上主也會對你所喜愛的事或人加以保護。”

後來我母親將這句話真不曉得重念過多少次呢!按照母親所說,那時她想到費牧師的那話,以及對上主立下的約。即已堅信上主的應許和護佑,生活中當即恢復了寧靜。

此後,雖有日本飛機多次到陝西來投彈,軍隊的調動往來頻繁,郵件也漸斷絕了,但她相信上主的慈手必會遮蓋保護。(下期續)![]()

A Song of Salvation at Weihsien Prison Camp

Mary Taylor Previte

They were spilling from the guts of the low-flying plane, dangling from parachutes that looked like giant silk poppies, dropping into the fields outside the concentration camp. The Americans had come.

It was August 1945. “ Weihsien Civilian Assembly Center ,” the Japanese called our concentration camp in China . I was 12 years old. For the past three years, my sister, two brothers and I had been captives of the Japanese. For 5 1/2 years we had been separated from our parents by warring armies.

But now the Americans were spilling from the skies.

I raced for the forbidden gates, which were now awash with cheering, weeping, disbelieving prisoners, surging beyond those barrier walls into the open fields. Americans, British, men, women, children—dressed in proud patches and emaciated by hunger—we made a mad welcoming committee. Our Japanese guards put down their guns and let us go. The war was over.

Kathleen, Jamie, Johnny and I were the children of Free Methodist missionaries. We and all our classmates and teachers had been taken prisoner in the early years of World War II when Japanese soldiers commandeered our boarding school in Chefoo, on the east coast of China . As the Japanese army advanced, my parents, James and Alice Taylor, escaped to China's vast Northwest, where, for the remainder of the war, they continued their missionary work.

Before the war came, the fabled land of my childhood was a country of acient Buddhas, gentle temple bells and simple peasants harnessed to their plows. But across the China Sea , a clique of militarists was rising to power in Japan and pushing for expansion. They wanted “ Asia for the Asians,” with China , Manchuria and Japan cooperating under Japan's leadership.

They struck first in 1931 with an “incident” in Manchuria , and within six months they controlled it under a puppet government. Next, Japan started nibbling at China , eating her, as Churchill said, “like an artichoke, leaf by leaf.” No Allied power was willing to use military force to stop the takeover.

As the Japanese continued to eat away at China , Dad and Mother were finding it increasingly difficult to continue their work in the Henan province in central China . The Japanese soldiers were cocky. When you pass through the city gate, you dismount and bow to us—that was the order. Twice, when Mother hadn't dismounted fast enough from her bicycle, soldiers struck her across the head with a stick.

So Dad and Mother took Johnny and me and headed for a breather in Chefoo, where the two older children, Kathleen and Jamie, were already enroller in school.

The Chefoo School was, more than anything else, a British school. Its purpose was to serve the many children of Protestant missionaries in a vast, foreign continent—to be a tiny outpost where we could learn English and get a Western-style education. The original school had been 10 rooms and an outhouse, but by our time it had grown into a modern campus, a schoolmaster's dream, just a few steps off the beach.

When the Japanese army arrived in Chefoo, Latin master Gordon Martin was teaching a Latin noun to the Forth Form. “So,” he said softly, “here are our new rulers.”

Wearing steel helmets, bemedaled khaki uniforms, highly polished knee-high boots, and carrying bayonets, Japanese soldiers took up duty on the road in front of the school. Swords swaggered at their waists.

From an aircraft carrier in the harbor, a plane dropped leaflets in Chinese explaining “The New Order in East Asia .”

The Japanese Army is coming soon to protect Japanese civilians living in China . The Japanese Army is an army of strict discipline, protecting good citizens. Civil servants must seek to maintain peace and order. Members of the community must live together peacefully and happily. With the return of Japanese businessmen to China , the business will proper once more. Every house must fly a Japanese flag to welcome the Japanese.

--Japanese Army Headquarters

There was no effective resistance. The New Order in Asia had arrived.

It was the schoolteacher in her, I think, but Mother believed in learning things “by heart.” And with so much turmoil around us—war, starvation, anxiety, distrust—she was determined to fill us with faith and trust in God's promises. The best way to do this, she decided, was to put the Psalms to music and sing them with us every day. So with Japanese gunboats in the harbor in front of our house, and with guerrillas limping along Mule Road behind us, bloodied from their nighttime skirmishes with the invaders, we sang Mother's music from Psalm 91 at our family worship each morning:

“I will say of the Lord, He is my refuge and my fortress; my God, in Him will I trust…

“Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror bu night…

“A thousand shall fall at thy side and ten thousand at thy right hand, but…He shall give his angels charge over thee, to keep thee in all thy ways…”

Our little choir soared with the music—“to keep thee in all thy ways…Thou shalt not be afraid…”

We children had also sat wide-eyed in Sunday school, listening to spine-tingling stories of such pioneer missionaries as David Livingston in Africa , John G. Paton in the New Hebrides , and J. Hudson Taylor in China .

Hudson Taylor was my great-grandfather. At 21, he decided to give up his medical studies in England to pursue a dream—to take the Christian faith to every province of China . He sailed to China in 1853, and it was he who founded the Chefoo School in 1881.

He did not believe in public pleas for money or elaborate recruiting drives. He believed in God—and miraculous results.

“We do not expect God to send three million missionaries to China ,” Hudson Taylor had said, “but if He did, He would have ample means to sustain them all.” Hudson Taylor founder the China Inland Mission, and God sent a thousand missionaries—and money to support them.

We Taylor children grew up on that kind of faith. Our father was the third generation of tailors preaching in China . It seemed only natural to us when, in early 1940, Mother and Dad left us at the Chefoo School and returned far into China to continue their work. After all, it was China's war, Japan's war. England and America were neutral.

I was 7 years old at the time. My brother Johnny was 6.

On the morning of Dec. 8, 1941 , we awoke to find Japanese soldiers stationed at every gate of our school. They had posted notices on the entrances: Under the control of the Naval Forces of Great Japan . Their Shinto priests took over our ballfield and performed some kind of rite and—just like that!—the whole school belonged to the Emperor.

There was reason enough for panic. The breakfast-time radio reported the American fleet in flames at Pearl Harbor and two British battleships sunk off the coast of Malaya . When we opened the school doors, Japanese soldiers with fixed bayonets blocked the entrance. Our headmaster was locked in solitary confinement.

Throughout the month, Mr. Martin, the Latin master, had been preparing a puppet show for the school's Christmas program, and as far as he was concerned the war was not going to stop Christmas. Mr. Martin was like that. With his puppet dancing from its strings, he went walking about the compound, in and out among the children and Japanese sentries.

And the Japanese laughed. They were human! The tension among the children eased after that, for who could be truly terrified of a sentry who could laugh at a puppet?

But with the anarchy of war, the Chinese beyond our gates were starving. Thieves often invaded the school compound at night, and, to our teachers' horror, one morning we came downstairs to find that all the girls' best overcoats had been stolen. After that, the schoolmasters took turns patrolling the grounds after dark, and our prep school principal, Miss Ailsa Carr, and another teacher, Miss Beatrice Stark started sleeping with hockey sticks next to their beds.

* * *

Meanwhile, in Fenghsiang, 700 miles away in northwest China , a Bible school student interrupted a faculty meeting and pushed a newspaper into my mother's hands. Giant Chinese characters screamed the headlines: Pearl Harbor attacked! U.S. enters war!

Mother was stunned. America at war! She had visions of the Japanese war machine gobbling her children—of Kathleen, Jamie, Mary and Johnny in the clutches of the advancing armies. She knew the stories of Japanese soldiers ravishing the women and girls during the Japanese march on Nanking . Numb with shock, she stumbled to the bedroom next door and fell across the bed. Wave after wave of her sobs shock the bed.

Then—it might have been a dream—she heard the voice of Pat Ferguson, her minister back in Wilkes-Barre , Pa. , speaking to her as he had when she was a teenager, saying. “ Alice , if you look after the things that are dear to God, He will look after the things that are dear to you.”

In later years, she told the story a hundred times.

“Peace settled around me,” she said. “The terror was gone. We had an agreement, God and I: I would look after the things that were dear to God, and He would look after the things that were dear to me. I could rest on that promise.”

In the years to come, she said, as Japanese bombs fell around them and as armies marched and mail trickled almost to nothing, “I knew that God had children sheltered in His hand.”(to be continued...)

(英文原文經原作者同意在本報刊出)